On the surface the abdomen has no special outside structures, but is the center for digestion and reproduction (for drones and queens). It also houses the sting, a powerful defense against us humans.

Contents |

Wax Scales

Honey bees produce wax on their abdomens as scales

Workers around 6-12 days old can produce wax scales in their four pairs of wax glands. The glands are concealed between the inter-segmental membranes, but the wax scales produced can be seen, usually even with naked eyes. The scales are thin and quite clear. After workers chew them up and add saliva, it becomes more whitish |

Digestive tract

The digestive tract of the honey bee

Tracheal system (silver-looking networks) on the midgut of a worker. The tracheal tubes branches smaller and smaller untill it goes into indivudual cells directly to deliver oxygen.

The digestive tract is rather typical for an insect. The esophagus starts near the mouth, goes through an opening in the brain, through the thorax, and enlarge near the end to form the honey crop, which can expand to quite a large volume (nearly half of the abdomen in a successful forager). There is a special structure called preventriculus near the end of the crop. The proventriculus has sceleritized teeth-like structure, and also muscles and valves. These structures allow the workers to remove pollen grains in the nectar, and also stopping the backflow of food being digested into the crop, ensuring that the nectar is never contaminated. The contents of the crop can be spit back into cells, or feed to other workers, as is the case of nectar collected by foragers. The ventriculus (midgut) is the functional stomach of bees and is the largest part of the intestine. Malpighian tubules are small strands of tubes attached near the end of ventriculus and functions as the kidney, it removes the nitrigen waste (in the form of uric acid, not as urea as in humans) from the hemolymph and the uric acid forms crystals and is mixed with other solid wastes.The rectum is also quite expandable (just like the crop, and both are extoderma structures, and both are lined with a chitin layer, enabling workers to refrain of defecation for up tomonths (for example bees in Michigan here might have their last defecation flights in November, and then again in March the next year). |

Sting

The exuded sting with a small drop of venum on it.

|

A worker bee trying to get away after stinging. The sting has barbs preventing the sting to be pulled out, part of her digestive system is seen dragging behind her.

|

|

Once a worker bee stings, the bee tries to get away. The sting has barbs preventing the sting to be pulled out. The sting apparatus breakes off and is left behind. The sting, venom gland, and muscles controlling the gland, will work autonomously to pump venom into the victim. Alarm pheromone is also released to “mark” the victim. This sends a signal to other bees to sting you again. |

|

Reproductive system

Ovary of a laying queen. Indivial ovarioles can be seen, with more mature eggs shown as yellowish. Egg cells move down the tube of overioles and become larger and more mature, eventually reaching the oviduct and being laid out by the queen.

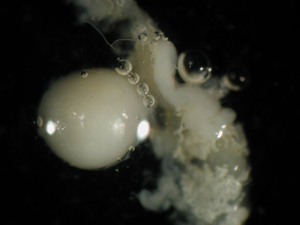

The spermatheca is shiny, perfectly speherical organ when the tracheal tissues are removed.

Important structures in the honey bee reproductive system include the ovary and spermatheca. In the ovary of a laying queen, there are indivial ovarioles, with mature eggs appearing yellowish. Egg cells move down the tube of overioles as they become larger and more mature, eventually reaching the oviduct and being laid out by the queen. The spermatheca contains the sperm from the queen’s single mating flight during a one week window around the age of 6-16 days. She will use this sperm to fertilize all the eggs produced in her lifetime. The sperm inside can live up to 4 years. The spermatheca is covered with a rich network of trachea. Once removed, the spermatheca is a shiny, perfectly spherical organ. In un-mated queens, the spermatheca will be clear. Queen breeders learning to use artificial insemination will sometimes check the spermetheca color in a sample of inseminated queens to see if their technique is working. |

Source:

Page text and photos authored and Copyrighted to Zachary Huang, Dept. Entomology, Michigan State University.